After another round of heavy, unpredictable rain moved through Los Angeles, the same frustration returned across Fairfax and Melrose:

Streets flooded.

Storefronts pooled.

Traffic crawled through standing water.

And the question always follows:

Fresh music, bold entertainment, and men’s fashion—one tight email a week.

“Why does this keep happening here?”

The answer isn’t just storm drains.

It’s geology.

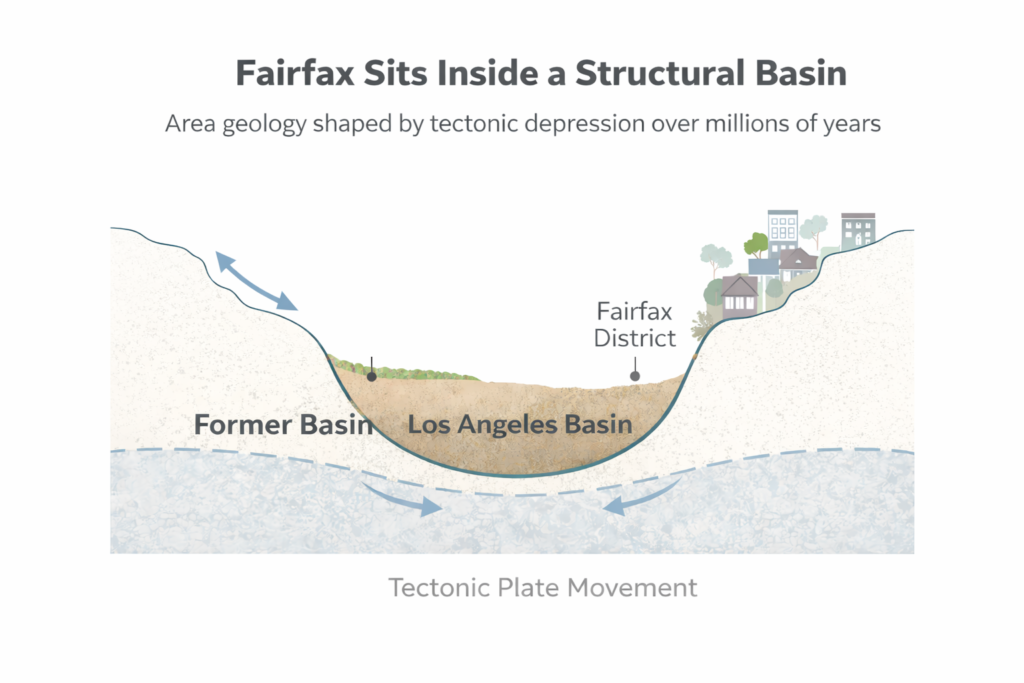

Fairfax Sits Inside a Structural Basin

The Fairfax District lies within the Los Angeles Basin, a massive structural depression formed by tectonic movement over millions of years.

This isn’t flat land.

It’s a bowl.

Water naturally flows toward lower elevations, and parts of Fairfax, Melrose, and the Grove corridor sit in one of those subtle low zones.

When intense rainfall hits in short bursts — which recent storms have delivered — runoff from slightly higher surrounding neighborhoods funnels inward.

If rainfall intensity exceeds drainage capacity, even briefly, water accumulates.

That’s not failure.

That’s gravity.

It’s Only Been Paved for About 100 Years

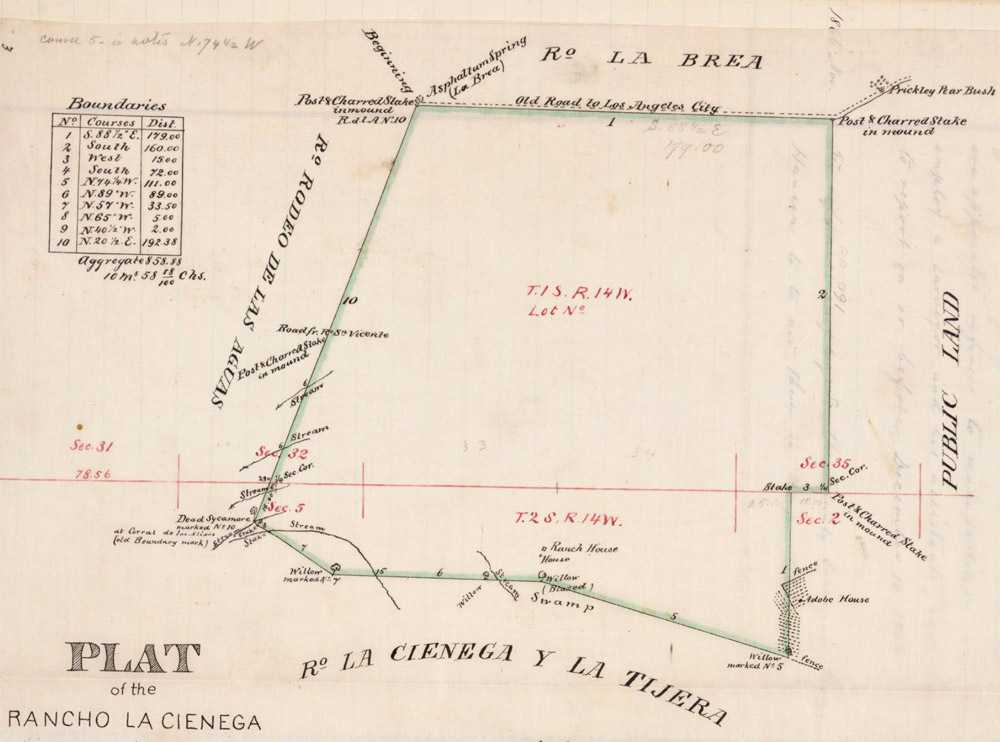

Image credit: Miracle Mile Residential Association.

Modern Los Angeles feels permanent.

It isn’t.

A century ago, Fairfax was open chaparral basin, seasonal marshland, and oil seep terrain.

In geological terms, that’s yesterday.

We replaced permeable soil with concrete.

We buried natural drainage paths.

We flattened wetlands that once absorbed rainfall.

Concrete doesn’t absorb water.

It redirects it.

And when you redirect water inside a bowl, it pools.

“La Cienega” Means The Marsh — And That Wasn’t an Accident

Look west.

Image credit: lastreetnames.com.

La Cienega Boulevard translates to “the marsh” or “the swamp.”

Early settlers named it based on what they saw: shallow groundwater and saturated terrain.

We didn’t rename the land.

We just covered it.

The Buried Creeks Still Shape Today’s Flooding

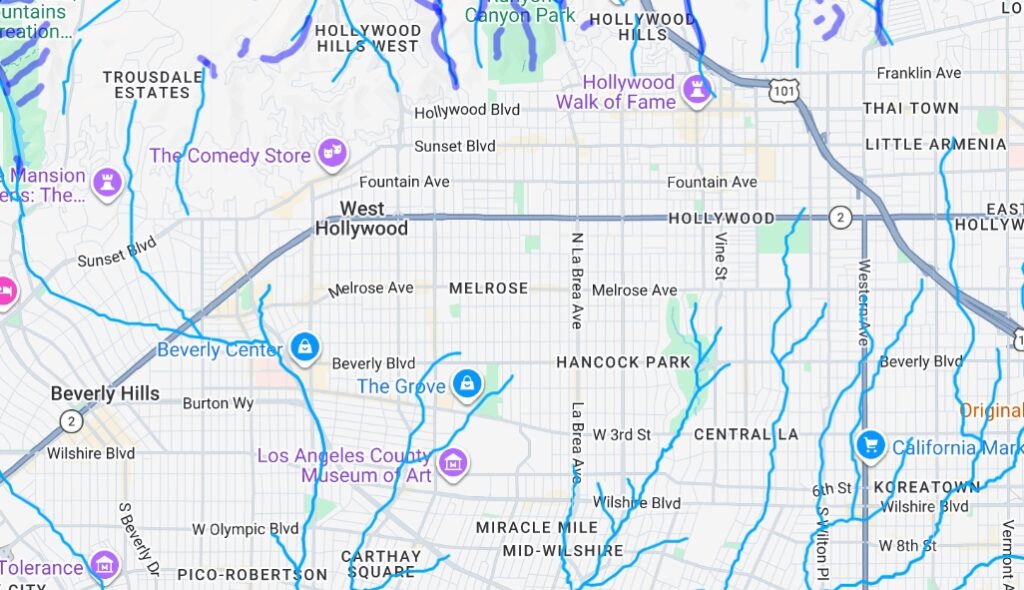

Historic runoff maps show multiple drainage paths threading through Fairfax.

Courtesy of lacreekfreak.wordpress.com.

Three visible stormwater channels either originate or converge in this area before continuing south toward Miracle Mile.

Historically, small creeks moved through:

- The Fairfax corridor

- La Brea

- Hauser

- Near Rimpau

- Through what is now The Grove and LACMA

Many were paved over or routed underground as the city expanded.

But the topography didn’t change.

Water still attempts to follow those original routes.

When rainfall is light, you don’t notice.

When rainfall is intense, the basin reasserts itself.

Check out the interactive creek map: See former and current creek paths across Hollywood and Mid-Wilshire — including runoff lines that converge near Fairfax.

Open the Interactive Creek Map

Courtesy of lacreekfreak.wordpress.com

The Tar Pits Confirm the Basin

Photo by Victor Atomic Lerma for INYIM, March 12, 2019.

The La Brea Tar Pits exist because this area historically trapped sediment, groundwater, and organic material in a low-lying zone.

That’s basin behavior.

During heavy storms, groundwater pressure rises. You may even notice increased seepage or that faint petroleum scent after rain.

The system is ancient.

The asphalt is young.

Why Recent Storms Feel More Severe

Photo by INYIM.

The issue isn’t just rainfall totals.

Recent storms have delivered:

- Short-duration, high-intensity bursts

- Harder-to-predict rainfall patterns

- Higher hourly accumulation rates

Urban drainage systems are designed for thresholds.

When rainfall exceeds those thresholds, surface pooling happens — especially in former marsh basins with buried creeks.

So what looks like:

“Why is this neighborhood broken?”

Is often:

“Why does water still follow gravity?”

The Line Worth Remembering

Courtesy of the Historic Los Angeles Facebook group.

We paved a marsh about 100 years ago and expected it to forget what it was.

It hasn’t.

When heavy rain hits Los Angeles, the Fairfax Basin behaves exactly like a basin.

And the bowl still fills.

Sources & Archival Materials

Historic maps and archival images referenced in this story include materials courtesy of the Miracle Mile Residential Association, the Historic Los Angeles Facebook group, and lacreekfreak.wordpress.com, used for editorial commentary.

From Los Angeles to anywhere built on former marsh, creek beds, or basins, these stories are often written into the land long before pavement arrives.

In the comments below, tell us what you’re seeing where you are.