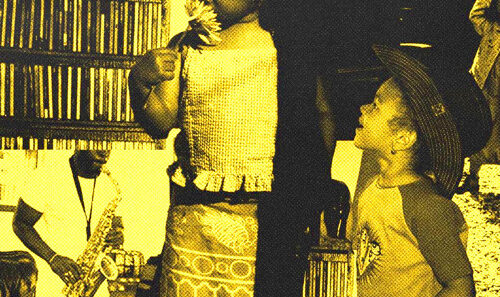

INYIM Media Archive Celebrating 35 Years! Producing Master Jimmy Jam Discusses The Making Of Janet Jackson’s Timeless ‘Rhythm Nation 1814’!

“We felt like we had… not a responsibility to say something, but growing up in the ’60s, whether it was the Vietnam War or whatever, it seemed like there was always someone commenting on it,” Jam says. “And that was a good thing. Why not use the powers we have as songwriters to bring some of those messages across? Rap music was doing it in a very strong way.”

INYIM WeeklyGet the good stuff.Fresh music, bold entertainment, and men’s fashion—one tight email a week.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.Musically, Jam and Lewis were already gravitating toward an edgier sound perfect for the new lyrical content. Clangorous yet syncopated, spliced with rock, hip-hop, and urban sound effects, the music matched the franticness of the modern world. While it derived partially from the New Jack Swing sound pioneered by producer Teddy Riley, Jam and Lewis were essentially updating what they’d always done.

“Growing up in Minneapolis, watching people like Prince, we saw that all ideas are valid, and color lines are blurred,” Jam says. “Rock guitar goes over funky beats, and keyboards replace horn sections. It was all of those things put together that became an incubator.”

What grew out of the sessions wasn’t quite the straight-up topical album some remember. In addition to reaching No. 1 on the Billboard 200, Rhythm Nation spawned seven top 10 singles, only one of which, the title track, had any kind of political leaning. The others — “Escapade,” “Love Will Never Do (Without You)” “Miss You Much,” “Come Back to Me,” “Alright” and “Black Cat” — were relationship songs that didn’t fit with trio of high-minded “message” tracks that kick off the album. The mix of personal and political, Jam says, was wholly intentional, and the album was sequenced with the heavy stuff up front.

They could have easily called it Escapade, Jam says, and swapped the stark cover shot for a nice color photo. That would have been the safe play, though the execs at A&M Records were fine with the tracklist and monochromatic presentation. In fact, Jam says, they didn’t raise a single objection until Janet needed a boatload of money for the half-hour video for the title track.

“She was asking for a million bucks or whatever,” Jam says. “They were like, ‘We haven’t heard any music.’ The story was that Janet took Gil Friesen, the president at the time, in a Range Rover and drove up the Malibu coast with him and played him three or four songs. I remember she called me three or four hours later and said we got the budget. How could you not give the budget—hearing those songs, riding in a Range Rover with Janet Jackson on the PCH in Malibu?”

Whether blasting out of a Range Rover sound system or streaming through computer speakers, Rhythm Nation 1814 — which was recently reissued on vinyl alongside several other Janet classics — holds up three decades later. Read on to see what else Jam has to say about the album’s genesis and legacy.

Janet was recently inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. How important was this album in terms of critics and audiences seeing Janet as a serious creative force?

Janet being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame was well-deserved. So many of the trends in music today and the idea of female empowerment on all musical levels owe so much to her. Her innovations in staging, from her headset microphone to the elaborate arena size theatrical sets, and groundbreaking music videos incorporating innovative dance steps have been, and are still being, emulated by all artists across the board, not just rock n’ roll. The Rhythm Nation album was designed to use music to inspire and inform people. She has total credibility as a songwriter and I expect to see, and welcome her, into the Songwriters Hall of Fame alongside us very soon.

Can you speak to how relevant the lyrics remain even 30 years later?

The fact that the lyrics remain relevant is a bit of a disappointment actually. It means we haven’t moved too far away from the prejudice, ignorance, hate and racial bias that we spoke about 30 years ago. I still believe the power of music is the healing force for all things. It transcends language, race, age, and unites all the commonalities that we have. It’s necessary like the air we breathe and we’re going to continue to use our gifts to try to change lives in a positive way.

Are there any tracks or outtakes that didn’t make the original project? If so, are there plans to do anything with those in the future?

There may be a couple of songs laying around that we didn’t ever finish but there’s no plans to do anything with those at this time.

Professionally, where was Janet Jackson at this point in her career?

She obviously had a lot of success on the Control album. There was pressure to follow that up, and an anticipation of what the next project would be… The thing that made it good for us was it had been three years since Control. We had no desire to try to follow up Control as much as make a new album. The difference was that when we did Control, we did it in Minneapolis, it took six weeks and nobody was paying attention. When we were doing this record, it took six months, we did it in Minneapolis and everybody was trying to hear something and give ideas. All of a sudden, everyone was interested. This album was much more under the microscope.

Where was she emotionally?

She was in a great place emotionally. She had begun dating Rene Elizondo, who ended up being her husband. Rene was a really good influence on her. She had done the things she talked about on Control. She had moved out on her own. She was making her own way. She was obviously making her own living. She was in a very creatively fruitful place. She had just discovered her writing chops. The mistake I always saw on her first two albums — or maybe not a mistake — was she just went into the studio and sang. She had no input into her records at all. A lot of it was probably her dad saying, “You should sing. You have a good voice. You should sing.” Rather than her saying, “I really want to sing.” The Control record, to me, was her saying, “I really want to sing, and I really want to be an artist.” Coming into Rhythm Nation, she’s hungry. She’s excited, and creative juices are flowing. She can’t wait to do this record. Everything had built up to this moment.

Is it true the label wanted her to make a record called Scandal, all about her family?

In 1989, as the world was going to hell, Janet Jackson was coming into her own. The pop star’s ascent and the planet’s downward slide intersected neatly on Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814, a socially conscious, sonically adventurous, commercially massive album released 30 years ago on Sept. 19, 1989.

Technically, Rhythm Nation is Janet’s fourth album, though her first couple don’t really count. It wasn’t until her third, 1986’s chart-topping Control, that the youngest Jackson truly gained creative freedom and stepped out of her family’s shadow, and on the follow-up, she pushed things even further. As with Control, she worked with the songwriting and production team of James “Jimmy Jam” Harris III and Terry Lewis, former members of the Time and architects of the “Minneapolis Sound” popularized by Prince in the late ’70s and early ’80s.

As Jam tells Billboard, no one went into Rhythm Nation looking to make a political record. The concept emerged as he, Lewis and Jackson watched CNN during breaks in the recording and found themselves shocked by the homelessness, violence, drug abuse, racism and general craziness plaguing America

Honestly, I’ve heard that story, but no one I can recall came to me and said, “We should do a record called Scandal.” I remember people coming to me and saying we should do a record called Control II. Everyone had ideas. It’s easy to jump on the bandwagon and have ideas after something is successful. At the end of the day, the creative team was simple. It was me, Janet, Terry and [executive producer] John McClain — and Rene Elizondo also. Let me include him on the creative mix. If the ideas weren’t flowing from that group of people, they weren’t really being listened to.

Instead of talking about her family, she commented on issues of the day. The hard-hitting music seems to match the subject matter. What came first?

The very first track we did was “Miss You Much.” That was kind of a hard-hitting song, only because I was using a different drum machine. Basically, everything sonically we had done on the Control record, I got rid of everything there, except for maybe one keyboard, called the Mirage. That’s the only keyboard I used in common, because I wanted it to be fresh and have a new sound. But “Miss You Much,” although the drums are different, it’s kind of the same sound we used on [1986’s] “Nasty.” I thought it was important there was something that was sonically familiar.

The hard-hitting part — we were going in that direction anyway, sonically. What really changed with the “Rhythm Nation” part was we then had a purpose. It was more directed. And it became more industrial-sounding. Trashcan lids, glass breaking, feet stomping — anything that felt like an army of people, that was sonically what we started going for once the lyrical concept started going in that direction.

How did the concept develop?

It really happened because we watched so much TV. There wasn’t DirectTV. It wasn’t 500 channels. There were maybe 20 channels that mattered. You had CNN. You had MTV, BET and VH1. And then you had ESPN. So that was it. That was what you watched. We ended up watching MTV all the time; then we’d switch it to CNN. Then we’d switch it to BET. You couldn’t help but somehow be impacted by the things that were going on. It was a crazy time. The Reagan years were ending. There were school shootings. There were all these unbelievable things starting to happen. We’re all sitting around watching this going, “Man, that’s messed up. Somebody needs to do something about this.”

What was it like recording in Minneapolis?

It was comfortable for her. There was no outside interference. There was no, “You need to make it more commercial.” It was us in our little vacuum, in the middle of the wintertime. All of that really contributed to what we came up with. The theme of Rhythm Nation came from literally watching CNN and reacting to what we were seeing.

And yet it’s not all politics and heavy stuff. The second half of the record is mostly love songs.

That was the great thing about sequencing the album. One of the things I miss about the idea of albums is we were able to sequence the album so “Rhythm Nation” comes first, straight into “State of the World,” straight into “The Knowledge.” After “The Knowledge,” she says, “Get the point? Good — let’s dance!” It’s not all doom and gloom. I thought that was pretty brilliant [of her] to do that.

Did you notice a change in Janet’s personality, or had she always been aware of these bigger issues?

It’s both of those things. She’d always been aware of the world around her, but she then felt empowered to actually talk about it and embrace it in her music. That was the difference. It had a lot to do with her growing confidence as a songwriter, and obviously her confidence in us as producers. Between Control and Rhythm Nation, we’d expanded our studio to a 48-track studio from a 24-track. Technically, we’d gotten better at what we did as producers and writers. Coming back to Rhythm Nation, I felt like we were all firing on all cylinders. We were hungry. We felt like sonically, we had a lot of new things to say.

The video component was key. It seemed like she was catching up to Michael Jackson in a way.

She grew up very similarly, loving musicals. She’d always talk about Cyd Charisse, Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire, and the Nicholas Brothers. Interestingly enough, Cyd Charisse and the Nicholas Brothers, she put them in “Alright,” one of the videos. She was able to pay homage to all these people she’d grown up listening to and admiring. But Janet always thought outside the box … She always had conceptual ideas of visuals in her head and what dances should look like. All those things were always running through her head. That was from her love of musicals growing up, much as Michael had. But this was her chance to do it. Not so much doing what Michael did, but doing her version of what she saw growing up, using those images to bring the songs across.

A lot of people talk about Rhythm Nation influencing much of the R&B music that followed in the ’90s. Do you think it was a game-changer?

Yeah, [it influenced] a lot of music I heard, particularly coming out of Sweden, quite honestly. Robyn talks all the time about the influence Janet Jackson records had on everybody there, sonically and style-wise. A lot of the music coming from Europe definitely embraced a lot of that sound and the sonic textures.

The album is sometimes labeled New Jack Swing, but it transcends that, bringing in elements of the Minneapolis Sound and everything you guys had done before.

We’re influenced by everything we hear. We really liked the records Teddy Riley was making at that time. They were fantastic. New Jack Swing — I always felt like “Nasty” was part of that. It has that feel. “Nasty” actually predates a lot of that New Jack Swing stuff. It’s just that we didn’t make 10 records that sounded like that. We made one record that sounded like that and then we moved on.” – Billboard.com