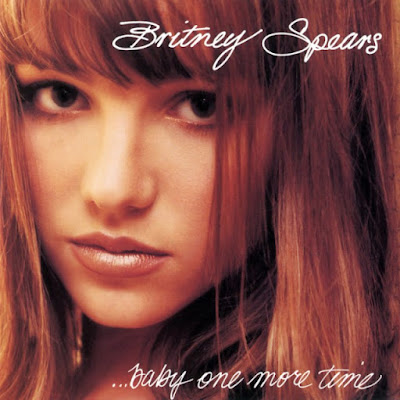

Zephrying since 1998 Britney Spears and her now legendary arrival into the musique industry is forever cemented as one of thee all-time greatest in Pop history!

“Britney Spears is the first thing you notice upon entering my childhood bedroom: a messily-taped 34-inch poster of a 17-year-old popstar with a million-watt smile. The Southern sweetheart is sitting on the back of a red pick-up truck in flare jeans and Skechers.

Fresh music, bold entertainment, and men’s fashion—one tight email a week.

The poster dates back to 1999, one year after Britney released her first monster hit, “…Baby One More Time,” one of the best-selling singles of all time. I must’ve been four years old when I first heard it. Those three opening keys, that wah-wah guitar — dun dun dun, “Oh baby, baby” — hypnotized me, along with the rest of the world. In preschool, it compelled me to choreograph dances and illustrate its lyrics with crayon scribbles like a possessed child. In 2013, it compelled me to steal that poster from a children’s day camp, which explains the tear where Britney’s left foot should be.

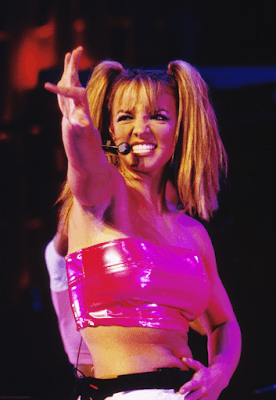

Few were left unaffected. And the music video — shots of Britney dancing around a high school, tapping her pink fluffy pen — only heightened reactions. Britney’s vocal fry registers as a baby alien with a sore throat, and it sounds good. Put that baby alien in a plaid skirt, give it some questionable lyrics, and you’ve got controversy. To me, she was the cool older kid wearing a belly shirt in the hallway. The pop princess didn’t appear as innocuous to nervous parents, watching kids tie up their shirts as Britney demonstrates in the iconic video. Some critics wrote off the pop star as a modern day Lolita. Excited musicians embraced “…Baby One More Time,” some even putting their own spin on the undeniable jam. It was unlike anything that preceded it.

The smash success of “…Baby One More Time” finished off MTV’s rock-focused era with help from the likes of *NSYNC, Backstreet Boys, “MMMbop”-ing Hanson, Christina Aguilera, and Spice Girls. MTV no longer catered to fans of grunge and alt-rock. They were looking to the new millennium and its teen-pop leaders.

“…Baby One More Time” is a confusing, almost uncomfortable work when broken down: a whole that comes alive in the tension of its parts, produced by none other than Max Martin, now known for his work with pop superstars like Ariana Grande, Taylor Swift, and Katy Perry. At the time, Martin was only a few years removed from his Swedish funk metal band, It’s Alive. Britney, on the other hand, had recently wrapped with the Mickey Mouse Club. Her Louisiana roots led her to pop radio and soul sensibilities, counting Whitney Houston as a big inspiration.

The hit was originally written for the Backstreet Boys and TLC, but got passed over to Britney when they declined. Britney’s delivery seems to channel and transform their styles into something totally new and uniquely hers. The result is funky, cinematic pop with R&B flourishes and fembot glitches. Britney and Martin struck a harmonious contrast, experimenting with a mishmash of origin and influence. Together, they would pioneer this female-fronted, maximalist mutant pop.

Visually, people were confronted with feminine aesthetics that didn’t usually appear together in pop culture. The Nigel Dick-directed video for “…Baby One More Time” positioned Britney as “innocent” but sexualized, and the “good girl gone bad” label stuck. She was open about her Christianity, but wasn’t shy about her sexuality. Her image was tied to her youth in a different way than those of the pop stars that came before her — Janet Jackson, Mariah Carey, Whitney Houston. It felt loaded, as if the promise of youth had been projected onto her.

It also revealed some creepy undertones within the pop music machine, its consumers and its players. Britney graced the April 1999 cover of Rolling Stone, photographed by David LaChapelle, laying on her bed in a bra and shorts, holding a Teletubby doll in one hand and a pink corded phone in the other. The article’s opening paragraph describes her “honeyed thigh,” “two little diamond earrings on each ear lobe,” “carefully applied lip liner,” “her ample chest, and her silky white shorts — with dark blue piping — cling snugly to her hips.”

Britney defended the photoshoot after the American Family Association called it “a disturbing mix of childhood innocence and adult sexuality.” She seemed to be the one controlling her appearance — she was supposedly responsible for her contentious tied-up shirt in the “…Baby One More Time” video. But to assign her full agency is to discount the power imbalance between a pop star pawn and the exploitative music industry. Britney’s image was fun and girly and somewhat tainted. And as of late, pop stars have taken it upon themselves to salvage her original aesthetic.

The overall appeal is hardly vintage — a timeless potion of youth, sex, and retrofuturism — but an evolving pop-culture landscape lets it settle into new meaning. Her proverbial moan-coo continued to shape pop music long after the initial onslaught of Britney wannabes that followed “…Baby One More Time.” Earlier Britney disciples include Lady Gaga and Miley Cyrus, but one of today’s most fervent patrons of ‘90s nostalgia is Charli XCX.

Since releasing her latest mixtape, Pop 2, last year, she’s been cultivating a community of young, diverse artists, aesthetically inspired by the past with a progressive vision for the future. The art for her recent singles revolve around colorful blobs that look like hyperreal models of wonky ‘90s graphics. One of those singles, “Girls Night Out,” sounds like an updated version of Britney’s 2001 track “Anticipating.” Another, “1999,” interpolates “…Baby One More Time” in its chorus. Max Martin actually contributed that line.

2018’s understanding of “teen-pop” isn’t as focused on age as it is on the excitement and novelty of being young. It takes what Britney built and applies it to the newly vogue notions of self-expression, inclusivity, and empowerment. There’s a keen self-awareness in repurposing Britney’s candy-coated cyborg funk.

“If you’re standing in some bar 10 years hence and ‘… Baby One More Time’ comes on the jukebox, you will smile. And you will move.” These sentences appear in the final paragraphs of Britney’s 1999 Rolling Stone cover story. “It looks like ephemeral pop might even be around in 10 years’ time…In other words, resistance is futile. Teenagers are driving our culture — and they won’t be giving the keys back any time soon.” At least they got something right.” -Stereogum.com